September 16, 2025 – A Tale of Two Thieves (or 3)— Acts #13

Acts 5:1-31

I was only a boy back at the oasis at Kadesh, barely old enough to carry water. We were at the border of the long-awaited promised land. Moses had sent 12 men to spy out the land before we entered. I was there when our fathers stood trembling and listened to the report of the spies, how the enemies were giants and the cities had massive walls. I can still hear their cries of fear that night, even after all we had seen. I watched as my parents and the other adults decided not to enter the land and refused to trust the Lord. And so that day God turned us back to wander, and for forty years I grew up beneath desert skies.

Now I am fifty years old. Almost all those who were adults then—my own father among them—lie buried in the wilderness. Only we who were children then remain, and now we are the “elders”, once again standing on the edge of the promised land.

I have seen God’s power again and again. I gathered manna in the morning from the desert floor. I drank water that gushed from a rock. I saw the earth open and swallow Korah’s rebellion whole (Numbers 16:31–33). I saw people suffer from the sting of fiery serpents in the camp and then be healed because they looked on the bronze serpent. And when Moses died, we all wept bitterly on the plains of Moab until our tears dried in the hot wind.

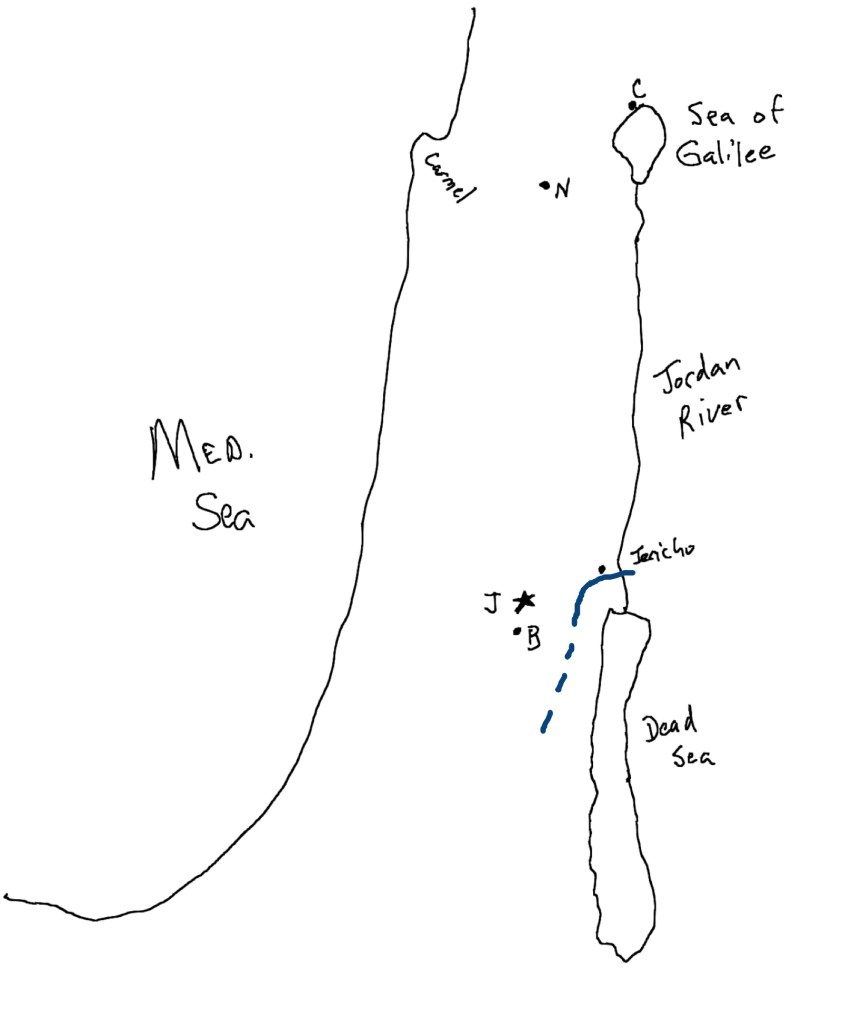

Through all those years, Achan and Eli were my friends. As children, we played together, racing between tents, chasing goats, all while looking forward to the land God had promised. We watched our fathers die and buried them in the sand, and we swore to God to do better. The three of us were brothers at heart, and we dreamed together of a house to live in with vineyards and olive groves. Just a month ago, we stood together and saw the Jordan River halt its flow as the priests stepped into it. We saw the waters rise up in a wall, and then we all crossed that river on dry land, just as we had crossed the sea back in Egypt when we were little kids. And just a few days later, we celebrated Passover in our new land together.

That was just over a month ago. Much has happened in the past week. For 6 days, we marched with the priests around the great city of Jericho, carrying the ark of Yehovah. They constantly blew their shofars as we circled the town, but we marched in silence, Eli and Achan alongside me, and then we returned to our camp. But on the seventh day, we circled the city seven times. Then the priests blew a long note on their shofars. Joshua repeated the instructions he had given us all week. It was time to shout and then rush in and take the city. But first, he repeated the warning that everything in the town was cherem, it was devoted to God. This was God’s battle, and all the spoils went to God. Only Rahab and her household were to be spared.

Achan, Eli, and I stood shoulder to shoulder, shouting until our voices were raw, and watched as those massive walls of the city crumbled like dried mud. It all happened just as God told Joshua it would happen. When the dust settled, we stood for a second in awe of the power of God. And the three of us looked at each other and smiled, rejoicing in the strength and power of Yehovah. And as we rushed toward the city of Jericho, Joshua’s words rang again in our ears:

“Keep away from the devoted things… All silver, gold, bronze, and iron belong to the Lord’s treasury” (Joshua 6:18–19).

As we moved through the city, I saw Achan pause near a shimmering robe. He caught my eye, and for a heartbeat, something unspoken passed between us. I dismissed it—we had been through too much to doubt one another. We gathered all of the gold, silver, and bronze for God’s treasury. And then we burned everything else in the city.

That night was quite the celebration. Having seen God take down this huge city made us feel invincible. Nothing could stop us now. But Joshua was not one to rest. The next day, he set his sights on the next city, Ai. He sent some scouts, and they returned and let Joshua know it was not nearly the size of Jericho. So they decided they only needed to take about 3000 troops. The troops were chosen by lot, and the three of us all hoped we would be selected so that we could see the power of God on display again. Eli was chosen, but Achan and I were not. So we prayed Yehovah’s blessing on Eli and sent our friend out with the small army.

They returned two days later. But they came back not in victory, but in shame. What should have been an easy battle ended in defeat and the death of 36 of our brothers. And one of the 36 who died was Eli, our friend since childhood. The news of his death struck me harder than any sword ever could. Achan and I sat in silence that night, staring into the fire, the weight of loss heavy between us.

That evening, Joshua lay face down before the Ark, and he asked the elders to join him. In mourning before God, we tore our clothes and put dust on our heads. But then God’s voice thundered:

“Get up. This is not the time to mourn a loss in battle, but a time to mourn the sin of Israel. You have sinned. You have taken what is mine. I will be with you no longer until you destroy the items that you stole from me.” (Joshua 7:11).

Someone had taken some of the treasure from Jericho. Someone had broken the cherem.

At dawn, we all assembled and divided into our tribes, awaiting God’s revelation of the guilty party. And the lot fell on my tribe, Judah. I looked at my friend Achan in shock, that someone from our tribe would have disobeyed God and brought shame on us. And then the lot fell on Zerah, our clan. This was hard to believe. So then our clan was divided again. I stood with my family, next to Achan with his family. And then the lot fell on my friend, Achan.

I was speechless. Joshua approached my friend and gently said, “My son, give glory to Yehovah and confess” (Joshua 7:19).

Achan’s voice trembled:

“It is true… I saw a beautiful robe, silver, and gold. I coveted them. I took them. They are buried beneath my tent” (Joshua 7:20–21).

Messengers returned with the treasures, the dirt still clinging to them. My heart broke. This was the boy who once shared my dried figs in the wilderness, who sang the songs of Moses beside me at the campfires, who mourned with me for Eli only yesterday.

In that valley, we stood together—Achan, his family, his possessions, and all Israel. We were all flooded with tears as the stones rose over my friend; the sound echoed off the valley walls like thunder. The pile of stones still stands in the valley that we call Achor, the valley of trouble. The stones stand as a monument to the God who sees all, even the secrets we bury deep.

That night, I could not sleep. I thought of the Red Sea’s walls of water, of manna’s sweetness, of serpents and mercy, of Jordan’s parted waters—all the times God had shown His power. And I thought of Achan buried beneath those stones and Eli, whose blood stained the ground at Ai. My friend’s hidden greed had cost us so much.

Now, as an elder of Israel, I tell you this: nothing—no robe, no silver, no secret sin—can be hidden from the Lord. As Adam and Eve could not hide in the garden, we cannot hide from His watchful eye. I have seen over and over his mercy and grace towards us. Growing up in Egypt, I would never have been anything but a slave. But he delivered me from slavery. He redeemed me. And through the long desert journey, he gave us grace after grace. A cloud covered us during the day to shield us from the scorching desert sun. A pillar of fire warmed us on the cold nights. He provided all our needs and delivered us from harm so many times. But His holiness is not to be taken lightly. His commandments are not to be broken. He is merciful, but he is just. He is full of grace, but a flagrant sin will not go unpunished. May we all seek to be obedient servants of you, Yehovah, our God most high.

Acts 4:36-37 Thus Joseph, who was also called by the apostles Barnabas (which means son of encouragement), a Levite, a native of Cyprus, sold a field that belonged to him and brought the money and laid it at the apostles’ feet.

Acts 5:1-6 But a man named Ananias, with his wife Sapphira, sold a piece of property, and with his wife’s knowledge, he kept back for himself some of the proceeds and brought only a part of it and laid it at the apostles’ feet. But Peter said, “Ananias, why has Satan filled your heart to lie to the Holy Spirit and to keep back for yourself part of the proceeds of the land? While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal? Why is it that you have contrived this deed in your heart? You have not lied to man but to God.” When Ananias heard these words, he fell down and breathed his last. And great fear came upon all who heard of it. The young men rose and wrapped him up and carried him out and buried him.

Acts 5:7-11 After an interval of about three hours, his wife came in, not knowing what had happened. And Peter said to her, “Tell me whether you sold the land for so much.” And she said, “Yes, for so much.” But Peter said to her, “How is it that you have agreed together to test the Spirit of the Lord? Behold, the feet of those who have buried your husband are at the door, and they will carry you out.” Immediately, she fell down at his feet and breathed her last. When the young men came in they found her dead, and they carried her out and buried her beside her husband. And great fear came upon the whole church and upon all who heard of these things.

The stories of Achan in Joshua 7 and Ananias with Sapphira in Acts 5 are separated by centuries, cultural contexts, and covenantal eras, yet they share striking similarities in their portrayal of sin, community holiness, and divine judgment. Today, I want to look at these two accounts side by side to illuminate how serious God is about obedience, how He treats hypocrisy, and to demonstrate how he consistently deals with people in both the Old and New Testament times.

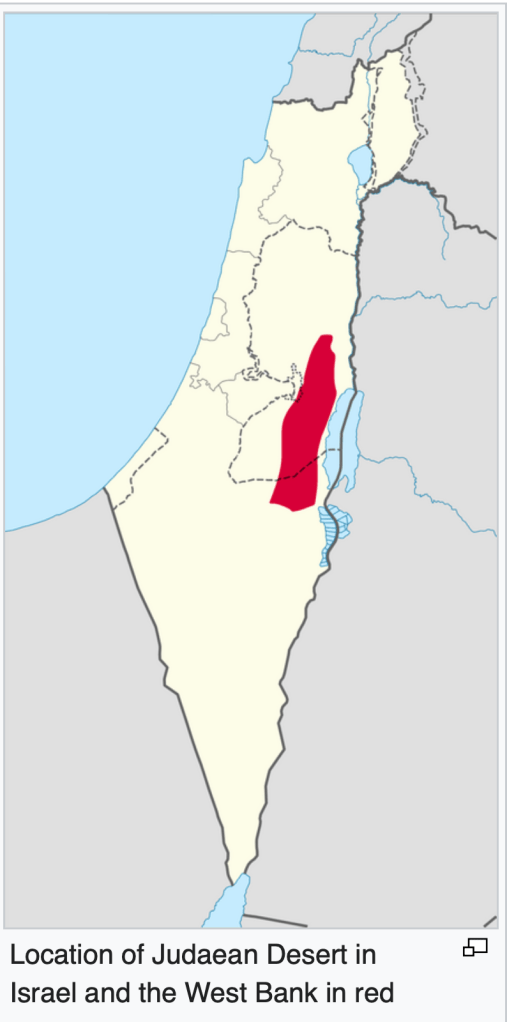

Achan’s sin occurred after Israel’s miraculous victory at Jericho. God had clearly commanded that all the devoted things—gold, silver, and valuables—belonged to Him alone (Joshua 6:17–19). This is the law of cherem. God would win the battle with Jericho, so everything that resulted from the battle belongs to Him. Everything that could be burned would be burned, given to God, much like a whole burnt offering is given to God by being consumed by fire. The precious metals would be given to the priests for use in the tabernacle and later the Temple.

Achan secretly kept some of the spoils for himself, burying them under his tent. His theft was an act of disobedience against a direct divine command and a breach of Israel’s covenant with God. They were God’s possessions. He stole them from God.

Similarly, Ananias and Sapphira’s sin was rooted in deceit. In the early church, believers were selling possessions to share with those in need. As we discussed last week, they understood the Biblical view of ownership. Everything belongs to God, and He entrusts some of His property to us to manage as stewards. Ananias and his wife sold a piece of property but secretly kept part of the proceeds while pretending to give the full amount. When Ananias came to Peter, he told Peter he had devoted the sale of the land to God. At that point, the proceeds from the sale belonged to God. Peter asks him:

Acts 5:4 While it remained unsold, did it not remain your own? And after it was sold, was it not at your disposal?

It would have been perfectly okay if Ananias and his wife had sold the land and decided to give God 20% or even 5% of the proceeds. They could have come and presented it to Peter, saying, “Here is a portion of the money from the sale of our land, use it for the poor.”

Instead, they wanted to look as righteous as Barnabus, giving 100% of the sale, even though they were keeping some. But the minute they said it all belonged to God, then it all belonged to God. Words are important. But they decided that no one would realize their deceit — they would appear righteous despite their deceit.

Like Achan, Ananias acted as though he could hide his actions from God and the faith community. In both cases, the sin was not merely the material act—stealing or withholding—but the spiritual betrayal: a failure to trust God’s provision and a deliberate choice to misrepresent the truth.

We see this same thing happening 1000 years after the defeat of Jericho and the sin of Achan, and 400 years before the events in Acts. Listen to the prophet Malachi speaking in 430 BC.

Malachi 3:8-12 Will man rob God? Yet you are robbing me. But you say, ‘How have we robbed you?’ In your tithes and contributions. You are cursed with a curse, for you are robbing me, the whole nation of you. Bring the full tithe into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house. And thereby put me to the test, says Yehovah Sabbaoth, if I will not open the windows of heaven for you and pour down for you a blessing until there is no more need. I will rebuke the devourer for you, so that it will not destroy the fruits of your soil, and your vine in the field shall not fail to bear, says Yehovah Sabbaoth. Then all nations will call you blessed, for you will be a land of delight, says Yehovah Sabbaoth.

Malachi said they were stealing from God. The Torah required a tenth of their money, crops, or herds that they accumulated to be presented at the temple. They were His. But they were neglecting the temple offerings. They were keeping for themselves what belonged to God. This is precisely what happened with Achan and with Ananius and Saphira. This is not an Old Testament concept, not a New Testament concept, but a forever concept.

The sin of Achan caused God’s anger to “burn against Israel” (Joshua 7:1). Achan’s private disobedience led to Israel’s humiliating defeat at Ai. It was a battle they should have easily won. They thought the enemy was small. They had just easily taken down the most fortified city in the land. They did not count on God being against them instead of for them in the battle at Ai. As a result, 36 Israelites died. The entire community suffered because of one man’s hidden transgression.

Sin affects the community, not just the individual. There is a collective responsibility to keep the covenant. If one member breaks the covenant, all are affected. In the same way, Ananias and Sapphira’s sin threatened the whole community of believers in Acts 5. Left unchecked, their hypocrisy could have seriously undermined the Spirit’s work. Achan was stoned to death. Ananias and Sapphira fell dead immediately. Acts 5:11 notes that “great fear seized the whole church,” indicating that God’s swift judgment preserved the integrity of the Christian community. Both episodes emphasize that individual sin can have communal consequences.

In both accounts, God’s judgment was immediate and severe. For those who seek to draw a clear distinction between God’s actions in the Old Testament and the New Testament, this should serve as a wake-up call. God has not changed.

These punishments may seem harsh by modern standards, but in their contexts, they served as dramatic warnings. It was the grace of God displayed in His dealing quickly with these sins before they caused worse problems. God’s holiness cannot be mocked, and covenant-breaking jeopardizes the mission of God’s people. We see in Paul’s letter to the church at Corinth a similar concern:

1 Corinthians 5:1-2 It is actually reported that there is sexual immorality among you, and of a kind that is not tolerated even among pagans, for a man has his father’s wife. And you are arrogant! Ought you not rather to mourn? Let him who has done this be removed from among you.

Everyone in town knew this man was flagrantly committing a sexual sin in their midst. Even the pagans disapproved of his actions. Yet the group of believers in Corinth chose to ignore it. Paul was very clear that he should be removed from the fellowship. Paul continues:

1 Corinthians 5:5-6 … you are to deliver this man to Satan for the destruction of the flesh, so that his spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord. Your boasting is not good. Do you not know that a little yeast leavens the whole lump? …

Paul hopes that by removing him, he might come to his senses, repent, and find salvation. Yet the congregation in Corinth is boasting instead of mourning this man’s sin. We see this in too many congregations today. They ignore flagrant sin in their fellowship when they should be mourning over those who refuse to repent. Paul warned that just as it only takes a pinch of yeast to cause the entire loaf to rise, it only takes a little sin to affect the whole church.

1 Corinthians 5:9-10 I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with sexually immoral people, not at all meaning the sexually immoral of this world, or the greedy and swindlers, or idolaters, since then you would need to go out of the world.

They are not to associate with sexually immoral people in their Christian fellowship. He clarifies that he does not mean the people outside the church. There is no such rule for avoiding sinners who are not in your fellowship. In fact, Jesus demonstrated that this is precisely who you should seek out. We should go out of our way to show love to and befriend those outside our fellowship who are flagrant sinners, remembering that we, too, were once the same. But for the grace of God, we would still be in that situation. How can we not want to share that grace with everyone? But for those in the church, there are different rules:

1 Corinthians 5:11 But now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or swindler—not even to eat with such a one.

For those who have joined your fellowship and persist in flagrant sins, you are not even to eat with them. By doing so, you are pretending that sin doesn’t matter and that God is not God. By ignoring the problem, you are making light of Jesus’ death on the cross.

1 Corinthians 5:12-13 For what do I have to do with judging outsiders? Is it not those inside the church whom you are to judge? God judges those outside. “Purge the evil person from among you.

And let me tell you, the church has done this wrong for so many years, assuming the position of judge of the world, telling the world they are sinners. It is not our job to judge the world. That is God’s job, and we are not God. We need to stay in our lane. However, for those who are part of our fellowship, it is not only our right but also our responsibility to judge them. The hope is that correction will lead to repentance and restoration. We have had this backwards.

Paul’s rebuke of the Corinthian church echoes the lessons of Achan and Ananias: sin, even when committed by one person, is never a private matter in God’s community. That was true 3400 years ago in the Old Testament. It was true 2000 years ago in the New Testament believers, and it is true today.

Israel would never defeat Ai until Achan’s sin was dealt with. The followers in Acts 5 could not continue to grow healthy if they tolerated hypocrisy. The followers in Corinth could not preach the gospel while tolerating open scandal.

Whether under the Old Covenant, at the birth of the church, or in the life of a New Testament congregation, God calls His people to holiness for the sake of His mission. Confronting sin—with grief, humility, and the hope of redemption—preserves the purity of the church and displays the character of a holy God.

When we answer God’s call to accept his gift of salvation, we enter into a covenant with God. He promises to forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. We promise to make Him our Lord, to turn over our lives to Him. We say, “Here, God, I give you 100% of my life.”

We lay our lives down at his feet, but are we really giving it all, or are we, like Ananias and Sapphira, holding something back? Once you say, “I give my life to you, God,” then it is His. If you try to take some of it back, then you are stealing from God.

Following Jesus is serious business. If we treat our obedience, or the obedience of others in our fellowship, lightly, the whole community suffers. Let us pledge anew our commitment to follow Jesus with 100% of all we have, mind, body, and spirit.