December 30, 2025 – Looking Back to Move Ahead—

A New Year’s Eve Message

A family anticipates the birth of a child. High School and College Students anticipate graduation. A patient anticipates test results. Just last week, children around the world had trouble sleeping due to the anticipation of Christmas morning. And in just a few days, 1 million people will gather in Times Square, New York, in anticipation of a lighted ball sliding down a pole.1

Anticipation carries excitement—but also tension—joy—but also uncertainty. And Scripture tells us plainly: God’s people are an anticipating people. From Genesis to Revelation, the Bible is not a story of instant fulfillment. It is the story of men and women who lived in the space between promise and completion, between the now and the not yet —trusting that God would finish what He had begun. Anticipation is closely tied to hope. And Hope is the subject of our first week of Advent. But the Bible does not use the word ‘hope’ the same way we do.

When we use the word “hope,” sometimes we mean“wishful thinking.” “I hope my team wins the game.” “I hope I win the lottery.” And in these instances, this hope may be a reasonable expectation or not. One of my grandchildren said last week, “I hope it snows for Christmas.” She can wish, but living in Northwest Georgia, it’s unlikely to happen. A farmer plants seeds in the spring and optimistically hopes for a good crop. My friend can say he hopes Georgia wins the playoff game this weekend. And based on their record and recent performance, it is certainly much more likely to happen than for Kate to see her snow. But there is a difference in the way the Bible uses the word. Biblical hope is not wishful thinking or optimistic thinking. Biblical hope is a confidence that something will happen. It is not a likelihood, but a sure thing, because it is rooted in the character of God.

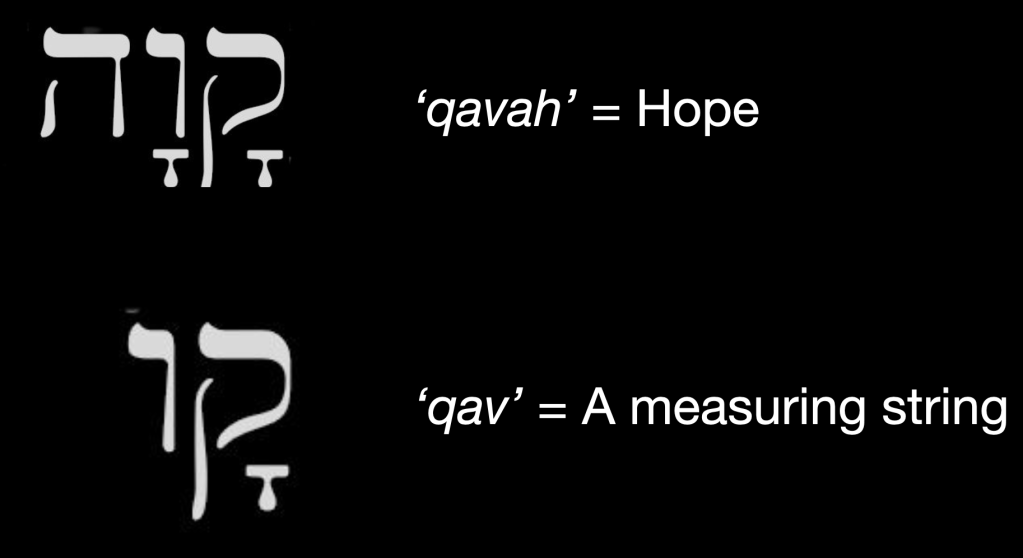

The primary Hebrew word translated as “hope” in the Bible is qavah. This word has a fascinating history. It is a verb derived from the noun ‘qav’. A qav is a measuring string. Today, any craftsman carries a measuring tape, but in Old Testament times and in Jesus’ day, they used a string called a qav. In Isaiah 44, the prophet is speaking about someone making an idol of wood, and he says,

Isaiah 44:13 The carpenter stretches a qav; he marks it out with a pencil.

We see this used still today. If you sew, you may have used a measuring tape. In Biblical Hebrew, this is a qav. And the ancient Hebrews made a verb ‘qavah’ out of this noun. But how do you get hope from a measuring string? Think about this qav. It won’t give an accurate measurement if it is not stretched out. The carpenter stretches out the string to measure. The seamstress stretches out the measuring tape. It must be under tension to be effective.

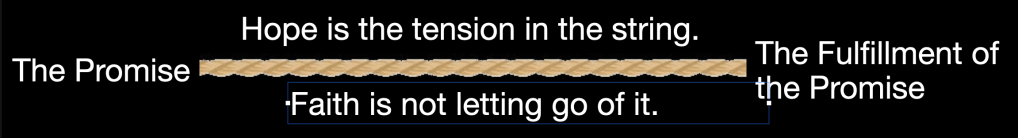

So the noun, qav, is a string stretched to tension to measure, and the verb they made out of it, ‘qavah’, is all about the tension produced in the process of waiting in hope. Hope in the Hebrew sense is all about that tension. Hope is living in the tension that exists between what is promised and the completion of that promise, between the now and the not yet. The tension of the time when you know something will happen, and when it does happen.

Abraham was promised a son, but there was that time of tension when all he had was the promise, and he wondered if he would ever have a son. Israel was promised a Messiah, but it had to wait over 400 years. We are promised the return of Jesus, and we live today in the tension of knowing that promise, even as 2000 years have passed and it has not yet been fulfilled. Again, our hope is not in something that might come true; it is a surety, for God’s promises always come true.

This is the essence of faith, holding onto the promises of God in the time between. Hope is the tension. Faith is not letting go.

Hebrews 11:1 Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not yet seen.”

The scripture says faith is the evidence of things that haven’t happened yet. But if you are the prosecuting attorney, how do you provide evidence of something that is yet to happen? Faith in God’s trustworthiness, faith in God’s promises, that is the proof of what will happen. God is always faithful to his promises; He is infallible. And that is all the evidence we need.

And it is not ‘blind faith.’ It is not as if our faith in God is just a mental decision to believe something we can’t see. We don’t just choose to have faith. Faith is itself evidence-based. This is the field of apologetics, which covers the evidence for the Bible and Jesus. If you are interested, I can recommend several good books on this subject. But the evidence before us is the Bible. These people who lived and experienced God in their lives present to us the evidence of thousands of years of God’s promises being fulfilled. The proof is all through this book. And Biblical history is increasingly confirmed each year.

For years, many historians doubted some of the Bible’s stories, saying that, since they had found no historical proof, they must not be true. They questioned the existence of a King of Israel named David. That was completely laid to rest when mention of David was found on a 9th-century stone tablet in 1993. Historians all agreed that the Hittite empire, often mentioned in the Bible, never existed, as there was no archaeological evidence. But they had to walk this back and change their books when they found the remains of their large capital city in Turkey. More and more evidence comes every year. You can visit museums to see many artifacts that confirm the Bible narrative.

But we don’t need all of those proofs. What does Jesus tell Thomas after he shows Thomas his hands and feet?

John 20:29 “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

“To not see and yet to believe.” I don’t have to see Jesus’ scars on his hands and feet. God doesn’t have to perform some sign for me to believe, for he has already done that over and over in the past, in the lives of so many in the Bible and in my life. “To not see and yet to believe” is to live in the tension of that hope in God’s promises that have not come to completion yet, but still believing, not because you can see, but because you have seen enough in the past to know that God is trustworthy. What you have seen in the past is the basis for your faith. Where does Paul say faith comes from?

Romans 10:17 So then faith cometh by hearing, and hearing by the word of God.

Paul says, “Faith comes by hearing.” But remember, Paul is a Jewish Rabbi. When Paul says ‘hearing’, he has in mind the Hebrew word for hearing, “shema”, which we talked about a few weeks ago. Shema means hearing and obeying; they cannot be separated. So Paul is really saying…

Romans 10:17 So then faith cometh by listening and obeying, and this by hearing the word of God.

And Paul is living in a day when God’s message was still primarily transmitted orally. Very few people had the opportunity to read scripture. Their primary encounter with God’s word was the spoken word. Now we live in a day when the scriptures are readily available to most people worldwide. Sadly, some people still only hear the word once a week, even though they have the luxury of reading it every day. God has given us the great gift of his abundant word in many ways. So if Paul were writing this letter today, he might say,

Romans 10:17 So then faith cometh by reading and obeying, and this by reading the word of God.

Here I am talking about the past when everyone else is thinking about the new year approaching. Are you looking ahead to what this new year will bring? Many of you will make New Year’s resolutions. And most who do will quickly break them. I read that fewer than 8% of New Year’s resolutions are kept. But we like to set goals. We are told to ask ourselves, “Where would you like to be in 5 years? How much weight do you want to lose in the coming year? How much money do you want to put in a savings account by the end of the year?” We make goals looking to the future. We are very future-oriented.

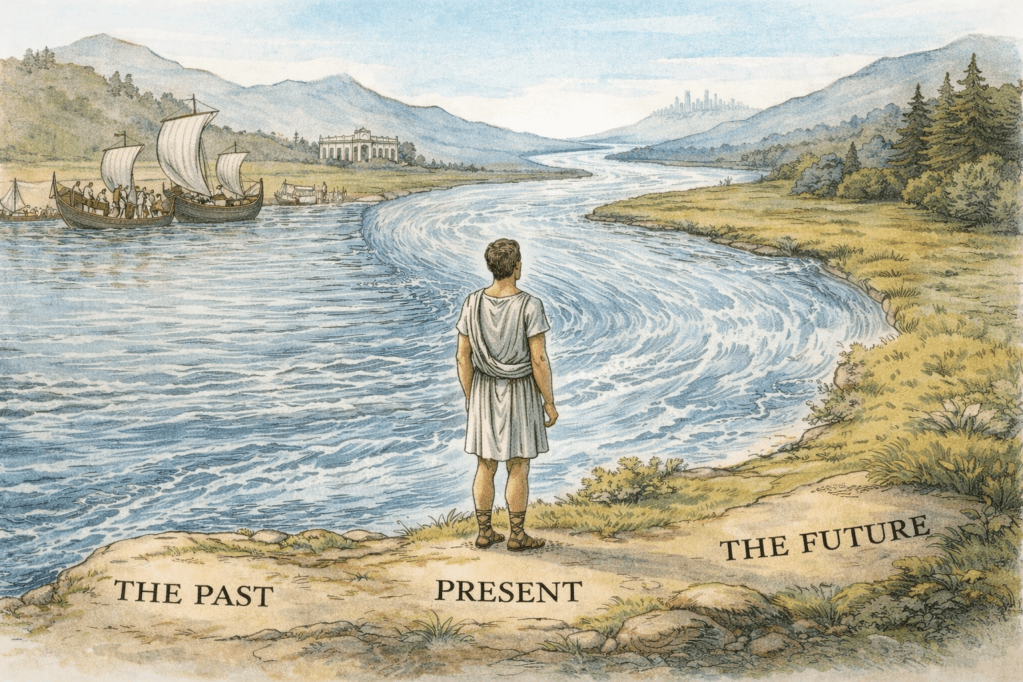

It comes from our view of time that we learned from the ancient Greeks. The Greeks saw time as a river. People stand somewhere along the bank, and where they stand is the present. What has already happened is downstream in the past behind you. The future is upstream, yet to pass by us, but it is already there, headed our way. If you have this view of time, you will be very confused when you read the Bible, because this is not the way the authors of the Bible thought about time. Take this verse in Job.

Job 19:25 For I know that my Redeemer lives, And at the last, he will stand upon the earth.

A great verse. A very poetic way of saying, “I know the living God who will redeem me. And in the future, he will come back for me.” But the Hebrew word for the future, the last days, is “אַחֲרוֹן” (acharon), which means “what is behind you.” For Hebrew thinkers, the future is behind you, which is the opposite of how we think: that the future is ahead of us.

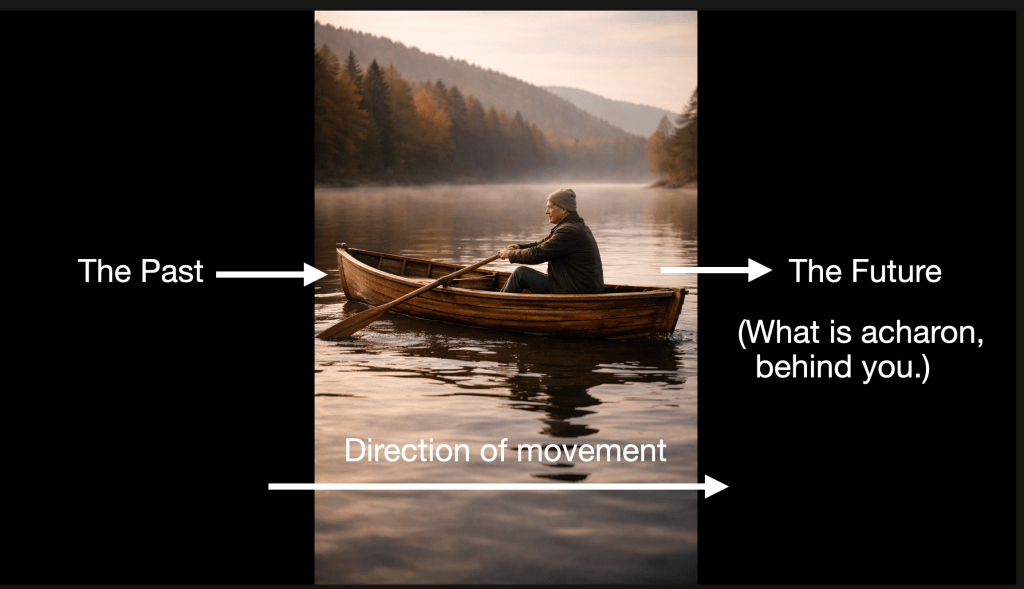

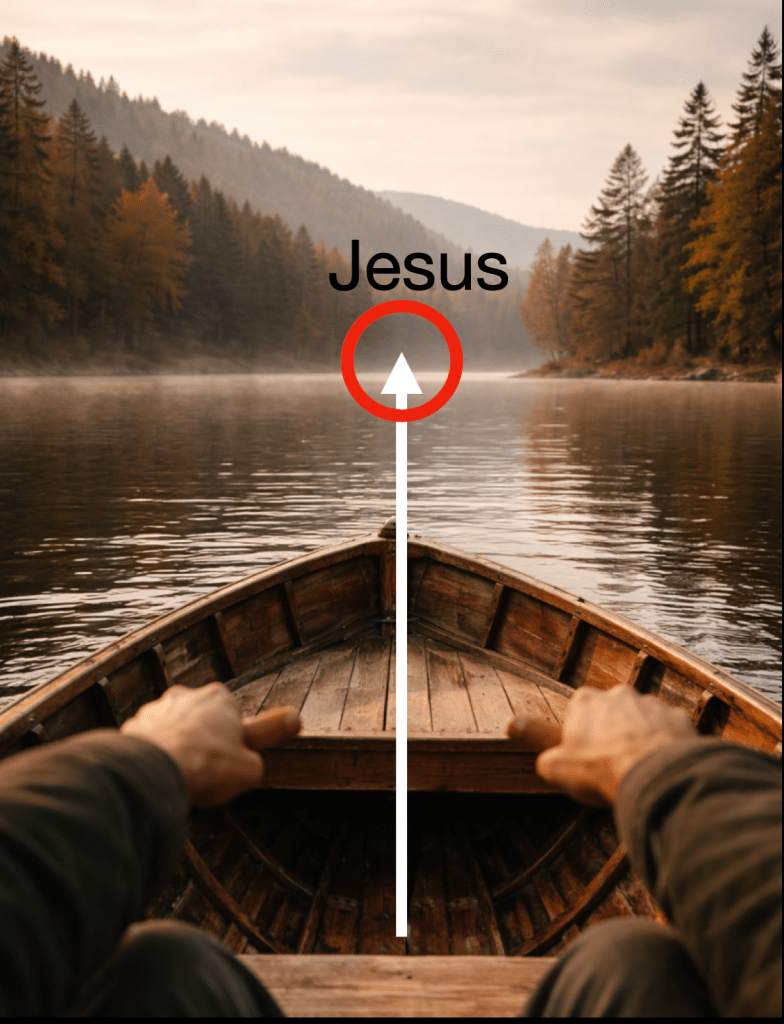

The best way I have seen this explained is by a 20th-century German theologian, H. W. Wolff. Wolff says that the Hebrew concept of time is like a man rowing a boat.2 How many of you have ever rowed a rowboat? In a conventional rowboat, you sit facing the rear of the boat. And this is the direction you move. You can see where you have been, but you can’t see where you are going. So in the Hebrew view of time, you have a full view of the past, but you can’t see the future, for it is all ‘acharon’ behind you.

So how do you maintain a steady course in a rowboat if you can’t see where you are going? I was taught that you focus on a point straight to the rear of the boat. As long as you keep that point directly behind the boat, you will travel in a straight line. So in the Hebrew worldview, you focus on a point in the past to direct your course into the future.

There is much truth here. We can not see into the future. We can only see the past. Perhaps this is why so many New Year’s resolutions fail. We cannot see what lies ahead, but we plan to reach this goal in an unknown future. We set goals where we can’t see. They become just wishful thinking. Perhaps we would do better if we operated using God’s view of time.

We can see the past. We have records of the past. We can see how we have behaved and how God acts. Instead of making goals based on an unknown future, we should, like the man in the rowboat, focus on a point in the past and use that to guide us. Find a worthy example in your Bible or in your own life and set that as your goal for the day.

God has given us many instructions on how to act, and he has, in scripture, given us many examples of men acting correctly and incorrectly, along with the consequences of each. If we look back to God and focus on Him, we can set a course that leads us to where He wants us to be.

Do you see the significant difference between this Hebrew view of time and the Greek view? In the Greek view, you are on the banks of the river. You really have no impact on the river itself. You are just an observer. Things happen and pass you by, and the future is fixed and coming downstream towards you. But in the Hebrew view, you are in the water. Like life, you can see the past but not the future. And you are not just a passive observer; you are active. You affect your path. You choose your direction.

Now, let’s tie this back into hope. Unfortunately, our English Bible translations often render the Biblical word for hope as ‘wait’ instead, as in this verse in Psalm 27.

Psalms 27:14 Wait for the LORD; be strong, and let your heart take courage; wait for the LORD!

That word ‘wait’ is “qavah,” our word for hope. And if we translate it as ‘wait for the Lord,’ we get the idea that we sit or stand passively, waiting. But if that is the case, then why do we need to be strong and take courage? God is expecting us not just to stand there and wait, but to be active, doing something.

So it is not wait’ but ‘hope’. And that preposition ‘for’ is the Hebrew ‘el’, which does not mean ‘for’ or ‘in’, but means ‘towards.’ But the translators said that “Hope towards the Lord” or “Wait towards the Lord” is not proper English. So they made it “wait in the Lord,” “wait for the Lord,” or “wait on the Lord.” Again, stand there and do nothing while God does everything.

That’s nice, but it is not the correct translation of “el,” and it is not how God typically works. Only a few remarkable times does God instruct people to do nothing while he works (before he parted the sea for the children of Israel to walk through is one of the few exceptions). But God calls people to act. Abraham, go. Moses, hold up your staff. Gideon go into battle. God wants to partner with us. So I would understand that verse this way:

Psalms 27:14 Hope towards Yehovah; be strong, and let your heart take courage; hope towards Yehovah!

Let’s look at a similar verse:

Psalms 37:34 Wait for the LORD and keep his way, and he will exalt you to inherit the land;

Here we see the same beginning, which I would translate as “hope towards Yehovah.” And the psalmist says, ” Don’t just stand there, but keep his way, follow his path, do as he commands. Hope is a proclamation of our faith in Him that causes us to draw near to Him in obedience. And how does God respond when we hope towards Him? One more verse in Psalms:

Psalm 40:1 I waited patiently for the LORD; He inclined to me and heard my cry.

“Waited patiently” is a translation of the Hebrew ‘qavah qavahti’, literally “I hope hoped.” The repetition is for emphasis, so you could say, “I hoped hopefully.” And how does God respond to our hope? Remember the qav, the measuring line that must be stretched out to work? And remember how qavah, the word for hope, is like that stretched-out line? If we hope towards God, if we are willing to live in faith in the tension of his promises, then God will stretch out towards us. (“Incline” is from the Hebrew ‘natah’, which is a verb that means “to stretch out, spread out, extend, incline, bend,” We see this in Jesus’ most famous parable, the Prodigal Son. Do you remember when the wayward son finally came to his senses and decided to go home?

Luke 15:20 And he arose and came to his father.

And how did his father, who is symbolic of God, respond?

Luke 15:20 But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and felt compassion, and ran and embraced him and kissed him.

When the child walks in the direction of the father, the father runs in the direction of the son. This is what God does. If we can hope towards God, being faithful in obedience to Him, stretching out towards him, then He will stretch out to us. Skip Moen says, “God never tires of our desire to come to Him. More often than not, we stop moving toward Him. We become believers in the divine rather than pilgrims to the divine.”2

Do you want to experience hope to the Lord? Are you tired of making New Year’s resolutions that you will soon break? Then choose the Biblical method. Don’t make a goal for yourself in the future that you cannot see. Instead, look to the word of God that you can see. See how he acts in the past and how he wants us to act. Let that be the fixed point we focus on. Choose to follow that path. This is how the author of Hebrews said this:

Hebrews 12:1-2 And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith.

Jesus is your fixed point to focus on that you use to set your course. Look to the example of Jesus to guide your behavior. “Do this in remembrance of me” is not just about partaking in communion or the Lord’s Supper. Everything we do should be because we are remembering what Jesus did.

And don’t look at a year ahead. The only day that we can be obedient is today. Did he say, “Give us this year our yearly bread”? His mercies are new every morning. Jesus said, “Take up your cross daily.”

So do you want to lean into God this year and live in an active hope in the tension of his promises? Then I ask you to join me. I will be reading through the Bible, looking back to move forward. And I am not asking you to commit to reading through the Bible in a year. I am asking you to read through a portion on January 1. And on January 2, I ask you to consider reading through a portion that day. One day at a time. And if you miss a day, it is past; you can’t go back and live it again. But you pick up the next day in your obedience. If you are interested, let me know, and I’ll put you on the daily text stream.

Romans 15:13 Now may the God of hope fill you with all joy and peace in believing, so that you will abound in hope by the power of the Holy Spirit.

- January 1 was chosen by the Romans as the beginning of the new year in the calendar popularized by Julias Ceasar (the Julian Calendar), as that was the day the Roman Consuls began their year to align with new leadership and the lunar cycle closest to the solstice. January became the name of the month after the two-faced Roman god, Janus, who looks backward to the past and forward to the future. A correction to this calendar in 1582 became the calendar we use today, as instituted by Pope Gregory XIII. The change caused the day following October 4, 1582, to be October 15th, not the fifth. Of course, God had long ago established his own calendar in Exodus 12, with the month of Aviv in the spring as the first month, and the 10th of that month as the day the Passover lamb was killed. There is no subsequent passage in the Bible that commands altering the calendar God established.

- Wolff, Hans Walter (1974) “The Concept of Time in the Old Testament,” Concordia Theological Monthly: Vol.45, Article 6.

- Moen, Skip. From “The Details” Skipmoen.com August 16, 2009.